Dear Lord Darzi,

I’m an SHO – sorry, CT1 – and have never had any inclination to become a GP. Hence, in my somewhat selfish way, I disagreed with, but largely ignored, your infamous polyclinic plans. Yet two funerals I attended this year brought into sharp focus why I, and thousands of doctors, feel polyclinics are a step in the wrong direction.

My mother’s younger sister met her husband at medical school in India and mirroring countless similar couples, came to the UK in the 1980s to start a family. Both worked as hospital SHOs for a time before becoming GPs in the north of England.

My aunt stayed at the same practice for many years, becoming a fast favourite with patients due to her caring nature and comforting smile. She raised my two cousins, the eldest of whom is now an F1. My uncle also excelled in his career and expanded his practice immensely. He pioneered many new initiatives, sat on various committees but never forgot his priority was his patients. His devotion to their care won him a profile in the Daily Mail as ‘Britain’s favourite GP’; secretly nominated by patients and staff. He found the whole thing embarrassing.

Both would routinely go far beyond the call of duty for their patients. Yet they would be the first to tell you that they were not exceptions. Their dedication to care, the relationships they built with patients and their place in the community is shared by GPs across the UK. Genuine family doctors.

Their diagnoses of two different cancers came years apart, but they died within three weeks of each other this summer. They were in their mid-fifties and desperately tried to keep working as long as they could. Both felt most comfortable in an NHS hospital when unwell.

I organised both funerals in the same crematorium. Its capacity was one hundred and on both occasions it was filled more than twice over. I enjoyed chatting to patients who simply felt ‘they ought to be there’. They emphasised how they regarded my aunt and uncle as honest friends, who they confided in, trusted and who never hesitated to tell them the truth.

A tall man with long hair, tattoos and a leather jacket, smiled when he thought about my uncle’s place in his life:

“I’ve had seven children, three wives and four houses...Dr X has been the only constant in my life!”

It is this one line that makes me fearful the British public’s relationship with their most important doctor will change forever.

My cousin wants to follow in her parents’ footsteps as a general practitioner. I want her to be able to experience the lasting relationships with patients my aunt and uncle did. I want her to be a constant in their lives.

Labels: medicine, NHS, polyclinics

Originally published in the June issue of Medical Student Newspaper.

THE very first plasty I wrote after graduating was entitled 'Pretend Doctor'. So it seems rather fitting that my last column as a foundation doctor (the first two years of training) carries the title of 'Real Doctor'. It has taken me two years before I felt ready to describe myself this way, but after last weekend I realised my two F-years have taught me more than I realised.

Some months I have to struggle to find something to write about. Other months it is immediately apparent. I didn't even have to think about the subject matter for my final column as I recently experienced one of the most memorable few days I suspect I will ever work through.

I am currently working in ITU and thoroughly enjoying it. I have been looking forward to this job all year and am considering it as a career choice, but it has only recently dawned on me how ITU is as much about death as it is about saving lives.

During my last weekend on-call, our unit had five deaths within about sixteen hours. None were unexpected, but all were quietly heartbreaking. Two stood out and taught me skills I know I'll find useful throughout my career. The first case was that of a 27 year-old man I shall call Stephen. Stephen had been in the unit for the best part of three weeks. He was admitted with a severe pneumococcal pneumonia on the background of pulmonary sarcoid. Over the days he had developed horrific ARDS with multiple broncho-pleural fistulae and bilateral pneumothoraces.

He was critically unwell for the majority of his stay, dramatically hypoxaemic and hypercapnic, before entering multi-organ failure. By the weekend I was on-call, he had four large-bore chest drains in his chest and quite astonishing surgical emphysema all over his body, puffing his face up like a beachball.

Stephen also had an amazing family. His siblings and parents took shifts to keep him company (only two visitors are allowed at a time) and made sure his favourite records were always spinning in his room. He had an enviable soul music collection, with Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson and Billie Holliday constantly vying for attention with the sound of Stephen's high-frequency oscillatory ventilator.

His family were understanding, grateful, calm, realistic, loving and clearly brought closer together by the slow deterioration of their son and brother.

On Saturday chest drains numbers five and six were inserted to attempt to further re-inflate his lungs. He now had three drains in each hemithorax. All six were on suction and bubbling furiously away.

About half an hour before I finished my shift, Stephen's nurse called me in a panic. One of the new drains had stopped bubbling after draining some blood. I realised the tube had a big clot in it and tried to unblock it. This proved somewhat tricky as the clot extended along the entire length of the tube. As I asked for a bladder syringe Stephen's blood pressure started dropping. His systolic fell from 90 to 60 in less than a minute.

Marvin Gaye provided the backing music.

With metaraminol in one hand and the bladder syringe in the other, I nervously kept his BP propped up. I thought this is probably the kind of thing my SpR should know about, but she was speaking to another patient's family. They were in tears, asking her to pull the plug on their loved one, yet she had to rush out midway.

Before she arrived Stephen went into PEA arrest and I started chest compressions. A cycle or two into CPR, Stephen still had no output. I was sure the chest drain was the problem but unblocking it was not easy. Suddenly an idea hit me, one that was both a product of following simple guidelines and attempting to diagnose the problem.

It was Stephen's 28th birthday. Meanwhile, Al Green was singing.

I pulled an orange cannula out of the crash trolley and plunged it deep into Stephen's left chest. A whoosh of air was followed by a recordable blood pressure and a pulse. I'd done it. A tension pneumothorax is such a film and TV cliché but for obvious reasons, it's as dramatic as hell.

I wanted to be the one to talk to Stephen's family. I am not sure why, was it anticipating the kudos I would receive after telling them of my actions? Or was it simply because I had developed a relationship with them and wanted to be involved? They were, as always, quite remarkable. They seemed genuinely concerned with thanking Stephen's nurse and me. Whatever bravado I had felt melted away as I realised that despite my proud moment, Stephen was in the same position he was in half an hour before.

By the time Stephen died, aged twenty eight and one day, within a day of this tumultuous episode, he had seven drains in his chest. A final blow was dealt when the transplant team, requested by his family, opened Stephen to find not a single viable organ.

Another death at the weekend was that of an old friend, a 70 year-old I will name John. I say old friend because I had known John for eight months. I met him in A&E and got to know him and his family during my four renal months, during which he was an inpatient for the entire duration. John had a past medical history as long as your arm and what I thought was the family from hell.

The entire renal team was wary of them. They were abusive, demanding, unfair and sometimes malicious. In fact I wrote about them once before because they drove me up the wall. John paid me a visit in ITU; his fourth admission there.

I warned colleagues: "be careful with that family" but soon realised that it was the renal ward they had trouble with, not any individuals, as they were perfectly friendly to me in ITU and indeed sought me out as someone to talk to as I was a familiar face. John became very sick very fast and suddenly I found myself in the breaking bad news mindset. Once again I took close family into the 'relatives' room' to suggest he had only hours remaining.

From the first time I met John he was bed-bound and withdrawn, but I learnt he was once a proud patriarch of a huge extended family. His two daughters and his wife remained by his side as the months had gone by and whilst I would once have ducked into the doctors' office to avoid a confrontation, now I saw three women losing the man of their house. I was overcome with guilt. I should never have let myself dislike these people.

John's wife, who had become quite motherly to me over the weeks and months, surprised me. She leapt up to hug me and said "I'm so glad it was you." I can assure you I wouldn't be glad if I was my doctor but I think one recognisable face in the bustle of ITU was reassuring.

Later I was with another patient and my SpR came over in floods of tears.

"What's wrong?"

"It's John, his whole family's there and it's just so sad. They're asking for you."

I nervously parted the curtains around his bed and found about twenty people crying, holding hands, saying prayers. It was clear that John commanded utter respect from those around him. It would have been nice to know him as his former self.

His wife brought me right into the middle of the throng and I felt like a complete imposter. Did they know how I used to feel about them? She told me that I always treated John like more than just a patient, that she would be sad she wouldn't see me again and that I will always be in her prayers.

I definitely did not deserve this. The feeling of guilt at receiving praise I was unworthy of, combined with the real happiness that I had made something of a connection with this family was unusual. I am sure I won't forget what John's wife said to me, perhaps even more so because of our colourful previous dynamic.

Corny or not, I can honestly say I will remember this weekend as a seminal point in my career. The moment I realised I am a doctor that can save a life - albeit only postponing death for a day - and that can make an emotional connection with a patient's family.

In the nicest possible sense, I hope you all experience an occasion in your career where you are forced to exceed what you thought were your limitations. When I finally got a day off several days later, I was exhausted and drained, but I had never felt more positive about my job. These are the experiences that teach you more than any DOP or CbD ever could.

After four fantastic years editing and writing Medical Student Newspaper, I can finally switch my bleep off. Good luck.

Labels: death, junior doctors, Rohinplasty articles

Originally published in Medical Student Newspaper.

BECOMING a doctor isn’t what it used to be. Communication skills, ethics, breaking bad news and familiarising oneself with the Job Centre would be foreign to medical graduands of the past.

Doctors have rapidly changed in their training and their demographic. Yet some things remain constant. We still have one aim - to cure the patient. And our roles as hospital leaders family doctors continue unchanged. Well…not so.

Within the health profession we are constantly under threat from government interference, nurses encroaching on our duties and hospital managers breathing down our necks. At work, we are no longer masters of our realm, but commodities.

So surely we can rely on a cheer that has buoyed generations of doctors, the love and respect of our thankful patients. Sorry, wrong again.

I am not referring to irate patients at the GP’s surgery nor pushy mums in A&E, but the particular section of the public that calls themselves the media.

You are, almost certainly, an avid reader of Medical Student Newspaper (right?!) So you might well believe that all newspapers regard doctors with the same awe and overt love that we do. But, do you know, you’d be wrong?

The simple fact is that the media hates you.

Make little mistake about this, for if you have not yet noticed it then bear it in mind as you survey the national headlines for the next few weeks. Soon enough you will see that doctors are viewed as over-privileged, over-paid, greedy, incompetent simpletons who sap money from the public sector.

Five years ago an article in the BMJ, which surveyed a small group of junior doctors, found that new medical school graduates were increasingly disillusioned by media attitudes to doctors, and ‘doctor-bashing’ became a familiar term.

The phenomenon has snow-balled. The phrase ‘doctor-bashing’ was coined some twenty years ago but the seeds were planted far earlier than that. The American writer Ambrose Bierce quipped at the turn of the twentieth century, “Physician, n. One upon whom we set our hopes when ill and our dogs when well.”

It is clear which particular breed of doctor has the roughest time at the hands of the journalist, the general practitioner.

Venerable, cardigan-wearing, bespectacled family doctor with a pot of lollipops. Dangerous, selfish, lazy fatcat. The criticisms range from mischievous generalisation based on a bad experience, to mean insults and fallacies.

Whereas here, doctors are thought to uniformly earn stellar salaries which should mean they are public servants with a job description the patients are free to adjust.

Why has the media decided to demonise the medical profession? The negative portrayal of doctors is now cited as one of the more demoralising aspects of working in medicine in the

Papers and television news love a scandal. Sensational stories about dodgy doctors are understandably popular in the press. However the rest of us soon become tarred with the same brush as Harold Shipman.

Key accelerants to the growing hatred of medics were the recent consultant and GP pay deals, offered by the Department of Health. The pay rises afforded to the average NHS consultant and the average NHS GP were indeed generous and whether they were deserved is, in fact, entirely immaterial. The fact is that doctors have born the brunt of media fury at the deals. Somehow we are to blame for a deal the government put forward; we are the bad guys for negotiating a good deal.

In a nutshell, GPs agreed a few years ago to take a small pay cut in exchange for avoiding out-of-hours work. Seeing as it has been established that doctors are lazy, columnists are keen to point out that they cannot get an appointment when they want. This means after they have gone to work, picked the kids up, walked the dog and gone to pilates. So somehow, their life and their commitments outweigh those of the GP, who should make the time.

Much as it warms my cockles, even a retrograde cynic like me will acknowledge the move away from the paternalistic ‘doctor-knows-best’ attitude was healthy. And it would be churlish to suggest that doctors don’t make mistakes. We should be open in our admission of mistakes, but increasing litigation makes this difficult.

I am particularly conscious of the public’s attitude towards doctors this month, as I was asked to be a guest on the PM Programme, on BBC Radio 4.

The PM research team had been reading an old issue of Medical Student Newspaper and came across the first piece I wrote as a doctor, which concerned ash cash, the fee paid on completion of a cremation form.

It is a very interesting topic and I wish debate ensuing the programme had been as stimulating. However it proved to be a very depressing experience. With some subtle editing I had been made to sound a little crass (mentioning ash cash is used on every day items such as food, rent and alcohol after a grieving daughter expressed her sadness at paying the fee when her mum died), but overall the experience was not too harrowing.

The BBC website and NHS Blog Doc (legendary blogger and former Medical Student Newspaper writer) picked up the story and became hotbeds for debate. The deeper concepts of coping with death as a house officer, the unpleasantness of funerals and the legal implications of what the cremation form means were not examined. Instead the comments from members of the public morphed into one hundred and eighty two savage assaults on doctors’ salaries (I made the mistake of referring to an F1’s pay as ‘meagre’), our arrogance, our insensitivity and even allegations of gross misconduct.

When commenters expressed outrage that they should pay for a funeral, I suggested they should also be annoyed at the undertaker, who charges far more than a doctor. No. Let one thing be clear - the anger was squarely aimed at the doctor, no one else.

Some alarming misconceptions came to light (that we demand the fee from relatives, that we’re paid overtime, that cremation forms are private work done on NHS time), but if I tried to point them out I was ignored or shouted down. A few valiant doctors also attempted to calm the furore but to little avail.

The more sinister reasoning behind the increased dislike of doctors is that, coupled with MMC, there is a concerted effort to undermine and break up doctors in the UK, so that as we are replaced by nurse practitioners, we have no unified voice or public support to support us.

Like that fat kid in school, now no one likes you.

Labels: Media, Rohinplasty articles

I WAS on the wireless today. It's not the first time - I was on Anita Rani's show on the BBC Asian Network talking all about porn, but that's another story. Today I made it, interviewed by Eddie Mair on iPM. Like most people, I despise hearing my voice, but it could have been worse. I was asked to comment as a piece I wrote for the paper about a year and a half ago was picked up. The topic under discussion was ash cash.

No sooner than one British establishment featured the DR, another did. Now I've really made it. The great Dr Crippen talked about ash cash too, which is why I thought I'd write this quick note.

The passage quoted on Dr Crippen's and iPM's blogs is tongue-in-cheek and I take any accusation of being insensitive on the chin, for it is deserved. But the passage should be taken in context, so do please read the rest.

Dr Crippen does indeed make the exact same point I did in the extended interview, hospital doctors who deal with death on a daily basis utilise coping strategies that are insensitive. When we talk about getting your ash cash from the ash point, or make jokes about celestial transfers to the big ward in the sky, it is merely a way of distancing ourselves from the fact someone has snuffed it. Crippo's right, we don't develop the same relationships with our patients that a GP might (well, polyclinics will see an end to that).

"I wish I was young again so that it could all be fun and “ash cash”, but I am no longer young. My skin is no longer Rhino-thick for now I understand what I am doing, and how important it is that I do it properly." [Link]

I enjoyed reading some time back that the venerable NHS Blog Doc describes himself as a curmudgeonly git, as this is how most of my friends would refer to me. Whilst I have maturing to do before I reach Crippenesque gravitas, it does not mean that youth eschews pathos.

Sure we joke and pick up our ash cash cheques, but I think we all spend a quiet moment contemplating the elapsed life we are signing off into the flames. In its great early days, Scrubs occasionally featured some great lines. JD looks at his first dead patient and says "he looked exactly the same, only completely different."

Moments like this, and fumbling awkwardly for a pacemaker across a cold corpse, are the experiences that stay with you and shape your development in medicine. But they're put away and covered by tasteless jokes at the pub. Just the way, I feel, it should be.

Labels: death, junior doctors

Originally published in the April issue of Medical Student Newspaper.

YET another horrible, horrible month rolls around and curse you Satan, curse you, I'm still alive.

Something's gone terribly awry as I am working a nightshift in A&E...when I don't have to. Yes I have voluntarily taken a locum shift in the hellhole that spat me out four months ago.

In fact this is just one in a line of locum shifts I am making a tradition. One nurse takes great pleasure in teasing me, "ooh look who's back, he who said he would never step foot in here again! You love it really."

How wrong she is. The question is then begged: why am I here? I don't seek to answer this in quite the metaphysical way Aristotle intended, but why am I seeing a perianal abscess at 1am? The only reason people do anything, money.

Once upon a time I used to pride myself on being quite an enlightened soul. Sure sure, this sounds funny NOW but only because you know me as the shallow git I undoubtedly am. However money never used to be high on my life's agenda.

I suppose any doctor would say the same - we're all in the wrong profession if money was our primary concern. But I really was other-worldly in my disinterest with money. I was generous and thought I would work for free as long as I had a roof over my head.

What complete gash. Over the last few months I have become the guy Scrooge McDuck aspired to be, well except for the swimming in your own money thing. That ducker still trumps me there.

I seem to spend my every waking minute thinking about money, whistling Pink Floyd's Money and carrying the FT. Just carrying it, I can’t read it. Now the reason I have subjected myself to additional A&E (along with some medical SHO) locums become clearer. I want money.

I think I can pinpoint where my slide from Buddha-like nirvana to cash-hungry Scotsman happened, and like just about everything in my life, it revolves around jobs.

It was only when I actually got a job that the immense stress on my shoulders became apparent. For months I had deluded myself that I was a chilled out cat, unaffected by job applications and an insecure future. In reality I never realised how much I was suffering.

I'm not alone. Perhaps 50% of my friends are still without employment come August. Feeling insecure about the future is a horrible thing and it had engendered a passion for money I had never experienced before.

With money, I felt I would be able to absorb the blows dealt to me by unemployment, I thought my Benjamins would help me roll with the punches. I spoke to senior colleagues about how much cash I would have to sleep on when I got to their level.

Horror. It turns out I'm earning more than my registrar. Sweet Jesus, several more years of hard graft and my pay will go DOWN.

Not only were my hopes of having a money-mattress dashed, I realised I wouldn't even have enough notes to light cigars with. 'Twas at this point I resolved to turn my efforts towards lining my pockets with the green.

Hence why you find me here, volunteering my time in the place I hate for the sum of £30 an hour. Sounds quite tasty, right? Certainly more than an SHO could expect to make in a permanent post. What if I just worked locum shifts? I calculate I could have an annual salary of £72,000. Not actually that impressive when I consider my best mate, who was at uni half as long as me, is on the same figure plus bonus and his company are buying him an Audi R8. I still drive my Nissan Micra.

As it happens, I know someone that decided to do exactly this, be a lifelong locum. He now owns five properties. The crucial difference is he is a GP. An agency I am registered with lists the following pay rates for hospital doctors: F1 - £21/hour, SHO £30/hour, SpR £34/hour and consultant £46/hour. The rates are the same irrespective of time or day.

For general practitioners, who will now be fully qualified five years out of medical school have slightly different rates: Mon to Fri - £100/hour, weekend - £125/hour and bank holiday - £200/hour.

The positives, let's concentrate on the positives. 20% discount at Nando’s. Back of the net.

Despite my enjoyment at reaping the rewards of locum shifts, they do represent a short-sighted waste of money by the NHS. A recent BMA survey shows that 30% of junior doctors are working on teams with at least one vacancy. My team has three. Hospitals spend money on expensive locums to cover shifts, but most of the time hapless SHOs and SpRs are strong-armed into ‘working a few extra hours’.

These vacant posts, all the more risible when thousands of SHOs are unemployed, are a legacy of MTAS and this year’s unnamed successor.

Consider two systems, both flawed. Years ago the SHO slaved away for three hundred hours a week, slept once a fortnight, knew all the patients and learnt bucketloads. Now I work a shift system, have an astonishing four handovers a day and there is practically no continuity of care for patients. Surely there is a middle ground?

As juniors’ training hours are slashed by the European Working Time Directive, and the time it takes to become a consultant is reduced by the government, we move towards a scenario where tomorrow’s consultants have perhaps a quarter the experience of present-day consultants. Likewise, practical skills suffer.

A renal job should mean getting to do loads of central lines. Sure…provided there is no team of specialist nurses inserting all the lines. They’re good at what they do, they’re cheaper than an SHO and don’t move on every four months, so why would a trust want a doctor doing these procedures? This way the number of expensive and troublesome doctors can be cut.

A superb plan. Except for the fact that I severely doubt the venous access specialist nurses will be around at 2am when a patient has crashing septic shock and needs a central line. But I will.

Labels: A+E, junior doctors, Rohinplasty articles

[via BoingBoing]

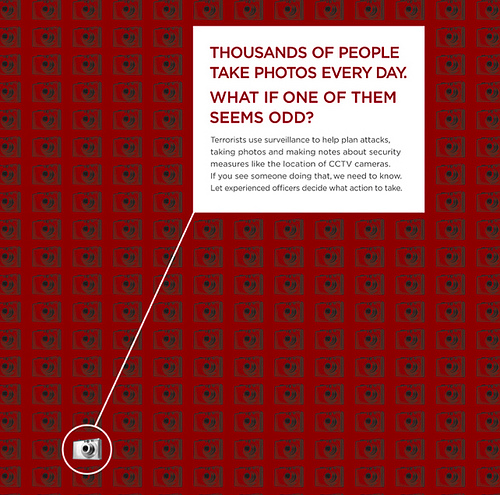

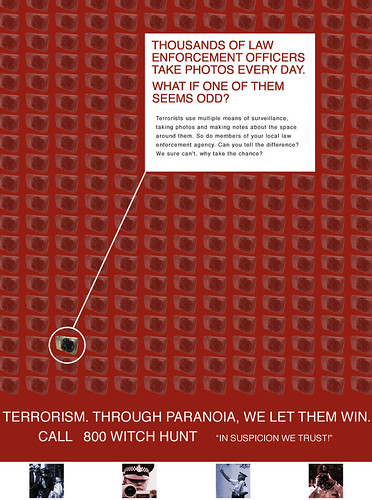

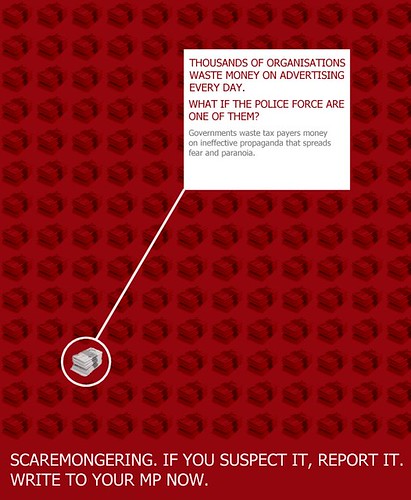

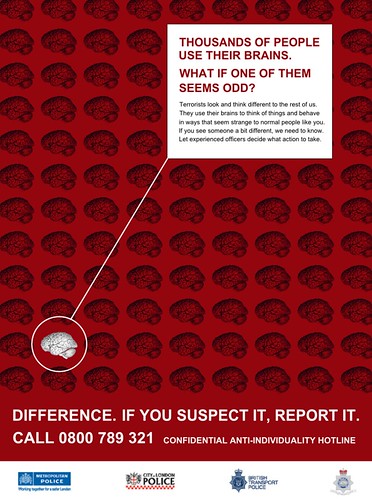

When I first saw V for Vendetta I was not overly impressed, but enjoyed the dark prediction of where London and the UK are heading. Perhaps we're one step closer. Many of you will have seen the asinine Met Police campaign that suggested we are too stupid to make common sense decisions about people with cameras and that somehow the Police are effective on acting upon tips. I love the fact that one poster alerts you to the dangers of people with more than one mobile phone. I might have to report every single Gujurati I know.

Here are some responses.

From Citizen.Kaned

Originally published in the March issue of Medical Student Newspaper.

I'M desperately trying to avoid writing about the rhino sitting on the elephant riding a unicycle in the room, again.

You’re bored of my ramblings about jobs, applications, unemployment and emigration. OK you’re bored of more than that. You’re bored of my tangential offal, lazy similes, dull subject matter and self-endulgent banter. But you’re still reading so haha up yours in your face pwned roflcopter lollerskates lmaonade lollercaust lollergeddon!!!!11!!!one

Hence I will endeavour to side-step my impending joblessness by telling you about the joys of renal medicine. Stop laughing.

I started this job having been a doctor for sixteen months and the step-up in responsibility was immense. I cover all renal, access surgery, dialysis and transplant patients and much of the time there is no registrar on-call with me. Just me and one of the country’s biggest renal units. Uh oh.

Getting used to dealing with critically unwell patients is part of being a hospital doctor and after my A&E resus experience I am feeling more confident. However an unexpected duty has been the referrals and calls for advice I have received from several other hospitals and local GPs.

At first I was apologetic and bumbling when GPs asked basic questions but as my ego grew in stature, I became more confident. Patients may still refer to me as ‘the one who doesn’t look old enough to be a doctor’ but on the other end of the phone my tenor tones could be anyone.

Recently I took a call from a teaching hospital, where an A&E SHO had seen a dialysis patient and wanted to arrange a transfer as he was ‘due dialysis’. It transpired he was septic and far too unstable to transfer, so I was surprised this doctor hadn’t sent him to ITU. Secondly, when I asked if he needed to be dialysed, she had no idea how one would decide this.

I walked her through the basics of fluid assessment and electrolyte control, much as I do with third year medical students. It was only when she gave me her name at the end did we both realise she had been an SHO at my previous hospital, several years above me and signing my DOPS.

Roles do often reverse when rotating around medical specialties. From the A&E grunt making the referrals, I am now taking them. I fight my natural tendencies and try not to be an arse, as I know how unpleasant referring to a dickhead is.

I don’t mind being called by house officers - I remember what it was like and I remember not needing to study much nephrology to pass finals. So I try to emulate the specialists I’ve enjoyed talking to and take time to explain renal physiology or the concepts of dialysis.

However when a surgeon calls, I have a little fun. Like the cardiothoracic consultant who asked his SHO to call me due to a rising creatinine. I suggested perhaps the new prescription of trimethoprim and the gentamicin level of 29 (aim <10)>

“Is the renal function normal?”

“Yes.”

“So it sounds like a urology problem, not a renal one.”

“But it’s renal colic.”

“No, it’s urology colic.”

A big poster at work tells me to ‘Save a Life, Give Blood’. Right on. Clearly some people think this is a cop-out. In light of the recent kidney-harvesting ring rumbled in India, I discovered a phenomenon I had never previously known about.

Donating a kidney is amazing. Doing this for a loved one is understandable, but I was immensely impressed when I first met a guy who was giving a childhood friend his right kidney. Yet nothing prepared me for the ‘altruistic donor’.

This is normally a man (in my experience) who wakes up one day and thinks “you know, I have too many kidneys”. He decides to undergo general anaesthesia and have half his piss-making equipment chopped out - for someone he will never meet. It’s quite astonishing - even a curmudgeonly git like me can be impressed by truly generous people, however loonie I think they are.

Labels: junior doctors, Rohinplasty articles

Originally published in the February issue of Medical Student Newspaper.

GOOD morning my friend! A warm good morning to you all. I love you, faithful readers, I love you with all my heart. But sadly I wish to commit heinous murder upon you at this present juncture in time, and indeed upon anyone that gits in mah way cos I is mad.

What, you might ask, has made such a normally cheery (I can be cheery) soul like me so irate? Did that A&E job finally make me crack? On the contrary, I finished it since I last saw you and have moved onto renal and transplant medicine. Wonderful wonderful.

Was it a bothersome patient what yanked my crank? No, I have been tolerating humans quite well recently. Is it the fact that my girlfriend’s Mum is staying with her for a month? Yes you’re quite astute, that’s probably not helping BUT it ain’t the root cause.

You’ve guessed it – job applications. I have brought you MMC news from the coalface over these last sixteen months, but at no point have I ever felt so low. Sure I’ll be cracking jokes in this piece, but secretly (and by writing this here, not secretly) I want to end my life. And I haven’t forgotten about murdering you either.

So what’s the dilly-yo? In a nutshell, for those shitbricks that haven’t been paying attention for twelve months, in 2007 the government unleashed its full wrath upon those lazy doctors and made tens of thousands jobless. 28,000 doctors applied for 15,500 jobs.

They did this by installing a woeful new application system, reducing the number of training posts despite record numbers of new graduates and not accounting for the many overseas doctors that work here but inviting a lot more in.

Thousands of junior doctors, many of whom are my friends, left the country. No one outside the rank of SHO seems that annoyed, so please do tell non-medics why they should be. Each of these doctors cost a quarter of a million pounds of taxpayers’ money to train. We, as a nation, have just let hundreds of millions walk out of the door. Australia, New Zealand and Canada’s gain is our huge loss.

I never thought I was the ‘leaving kind’. I love London and want to stay. That could be my downfall.

This year, it is worse. We were reassured but I think we all knew this to be false. However, last year we were provided with some ammunition. The Tooke Report, detailed in previous issues of this newspaper, made two key assertions. First, that government involvement with the training of junior doctors must stop. This has not transpired. Secondly, that the European Working Time Directive (which I recall being my first cover story as editor in 2004) is detrimental to junior doctors’ training by preventing sufficient hours learning on the job.

Reasons things will be worse this year include: many of the jobless SHOs from last year will be competing with this year’s glut for the same finite amount of jobs (in fact less, as much of the run-through allocation is filled). A recent ruling means that British-trained doctors are given no preference to overseas doctors when allocating jobs.

Overall, an estimated 22,000 applicants will compete for 9,000 jobs. Friends in other professional disciplines often seem confused as to why this is a problem. “Competition is healthy” they say, echoing what the government has been trying to dupe patients with. The key point is that in the UK, doctors can only train in the NHS, there is no alternative as there would be in a bank or law firm.

Continuing on from this analogy, consider my story, which I fear will be typical.

Today I received an email from Oxford Deanery, telling me I have been invited for interview in six days. I have heard, from an unsubstantiated source, that about five hundred applications for Core Medical Training were received by Oxford. They have 27 jobs to give away. So I am delighted I have been granted an interview.

But I have applied to both London and Kent, Surrey and Sussex because I, like a vast swathe of my colleagues, have been scared shitless by what happened last year. I have tried not to hedge my bets and end up jobless.

Let’s imagine I do well in the interview (you need a fertile imagination) and am offered a post. At this point I know none of the following: which hospital(s) I will be working in, my pay, my rota nor what firms I will be doing. Yet I have 48 hours and nor more to accept. If I don’t reply, I am assumed to have rejected the offer.

If I accept, I have to withdraw from all other Deaneries. The only problem is, London make their offers two and a half months after Oxford. So if I decide I want to wait it our for London – and then get offered nothing, I will have thrown away a job. Or if I hold out for London and get given a job I don’t want, I would rather have stayed with Oxford.

Taking our comparison back to banking or law, which companies do you know that would make a job offer with no details about the job whatsoever? Which industries can you think of where the boss doesn’t choose his own staff? And although some jobs make you move around the country, which gives a few weeks’ notice as to location, forcing the employee to sell, buy and move houses in a month?

Lastly, see if you know any banks or consultancies that would send this message to its employees. My ultimate boss, the government, sent all junior doctors a letter in January. It essentially said “don’t apply for anything competitive, you probably won’t get it. Don’t turn down any job applications, you will be lucky to even get one. Don’t be upset if you end up doing something you didn’t apply for, you should be thankful you’re employed.”

It amounted to: Aim Low. No fucking way any City firm says that to its employees. We’re being grown as a generation of ‘just passable’ docs. MMC engenders a culture of striving for mediocrity.

As I said before, I love London with all my heart. I want to make my life here. But in the last few weeks I have done some deep thinking. I had a hot bath recently – where I do my best thinking – and asked myself one question, “do I want to be a doctor?” I had toyed with the idea of leaving. Friends enquired at banks and they want to start me on £80-100,000p.a. But I realised I like being a doctor. It’s what I’m best at and I want to do it. This was a relief as I had started to have doubts.

The second question I asked myself was, “do I want to be a doctor in the UK?” I now know that without drastic change of far more than just the subject of this article – nurse quacktitioners, paltry consultant opportunities and the media’s attitude to us – I cannot stay here. The system has broken me.

Labels: junior doctors, MTAS, NHS, Rohinplasty articles

Originally published in the November issue of Medical Student Newspaper.

IT’S HALLOWE’EN in A&E. I start my shift at

Two out of six. As I can’t really take any credit for being male, I better try to enjoy my last month ‘working in emergency medicine’, which won’t be easy.

My first patient is what we politely refer to as a complete loon. I’ll call her Agnes and she’s visiting us from the local psychiatric hospital. Agnes has been sectioned for some time (don’t ask me what number) and hates the psychiatric ward she is on. It quickly becomes clear she is fabricating a story to get out of her ward. The psychiatrist must have seen her, realised he knows nothing about medicine and sent her to A&E.

It is, however, a little difficult to understand her as she has two Nicorette inhalers in her mouth. Not to mention the five Nicorette patches on her abdomen, her brown sunglasses, orange hair, five overcoats and two scarves.

Her sense of humour seems to be intact though:

“Doc, I’m telling you now, if you send me back there I will kill myself.”

“Well that’s convenient,” I replied, “because when people want to kill themselves we send them to psychiatric hospital.”

“In that case I don’t want to kill myself, I want to live!”

I’m rather in the mood for seeing some ghouls and ghosties tonight, and head to Minors in the hope of stitching up a pitchfork-laceration or vampire bite. I’m collared on the way by sister saying two are waiting in Resus.

I generally like working in Resus. You see, the overriding gripe I have about A&E is time-wasters. I have to resist slapping jackasses with nothing better to do with their time than ignore the sign saying “Accident and Emergency” and waltz in with problems they’ve had for years. But Resus patients (normally) aren’t faking it.

We’re short-staffed and I end up seeing two patients simultaneously. This is not only dangerous, it’s confusing. Luckily (for me, not them) they had almost identical problems (chest infections and fast AF) and pretty similar names, so I just said everything twice.

There’s no chance of me getting to Minors to see any pumpkin-heads after I’m finished with the two old boys in Resus, as “people are breaching in Majors.” Nurses always shout this at me under the impression I’m going to care.

A guy who felt his throat was closed for a minute, but is fine now. A girl who had chest pain but thinks it was wind. Then a bad-tempered Francophone jobseeker who broke his foot and was put in a cast two days ago, has a fracture clinic appointment in the morning and saw his GP two hours before coming to A&E. I explained broken feet do normally hurt, but he wasn’t satisfied.

In fact he turned out to be a real prick and I had to threaten to call security, in French, before he left. Not before shouting in Franglais:

“Where you from? How old you? You’re too yang bro! Je veut un autre médecin. Na, na, you got a long way to go.”

Whilst he was undeniably a tosser, he was probably right.

Where are those damn vampires? A frikking zombie at least, please Satan brighten my evening with something macabre.

The three others doctors on duty and myself wade through nursing home specials, neurotic parents, drunkards, asthmatics and more chest and abdo pains than you can shake a steth at.

2+ protein, 1+ blood, 1+ ketones. Ketones? I wonder what my blood glucose is? 2.9! Sweet, a new record. I mean, I think I’m going to faint. I rush dinner having wasted half my break investigating myself.

Back on the shop floor and I pick up the next card. “Limb problems” is the non-specific triage category and at last it’s a bunch of piss-artists in fancy dress. w00t!

My patient is not only dressed as an axe-wielding blood-soaked doctor, she’s an absolute hottie (I only mean that in a purely Hippocratical way).

Good-natured drunks are always fun so I act the part. Whilst taking a history I point to her friend in vampire garb and ask, “he with you?” and then examine her neck.

"What are you doing?" asks the friend.

"I need to know if she’s turned."

So she clearly has a thing for doctors and I will be spending the next half hour with her in a small room sewing up her elbow. I silently offer thanks to the Prince of Darkness as my mind turns back to that Lancet article.

However as she’s face-down for the stitching, I (tragically) spend most of the time talking to her friend, who wants to become a doctor. I give him half-mumbled answers as I get so engrossed in trying a fancy mattress-running suture combination on this hapless girl’s elbow.

When I’m done she bounds off without so much as a “thank you doctor, you saved my life” and an unexpected kiss on the lips, or a “how can I ever repay you?” and a lingering kiss on the cheek or even a “call me!” and an airkiss. In fact there was a distinct lack of kissing.

Somewhat confused as to how I could POSSIBLY have been turned down, I remembered I was lacking in brilliance, height, muscles and chiselled features. Soon I would lose my job title of emergency doctor as well. I mulled it over and decided I would rather undergo extensive leg-lengthening surgery than take another A&E job.

I finally allowed the chatter of friend-who-wants-to-be-doctor through and in an unusual display of paternalism, I put a hand on his shoulder and said “son, don’t do it.”

My shift would be up soon and I could grab a Rosie Lee’s Full English on my way home. Working nights eliminates your ability to do anything, so I’ll get back to working on my serum and saving the world from vampires next week. Right now, I’m just the daysleeper.

Labels: A+E, junior doctors, medical students, Rohinplasty articles

THE geniuses behind Medical Student Newspaper have produced some essential reading for all final year medics in the UK, in conjunction with doctors.net.uk. Quack contains all the knowledge one needs to apply for a Foundation post and more. Join the Facebook group.

My contributions included updated versions of stethoscope psychology, depraved revision, a breakdown of the MTAS saga and the WISE words below.

By the way, Medical Student Newspaper has won yet another award nomination. It is in the running for the Best Student Newspaper in the country at this year's Guardian Student Media Awards. Every year since the paper's inception has brought some silverware; fingers crossed.

How to be the coolest, most pimped-out, badass FY1 at your hospital

What you need to know as a first year doc and what you haven’t been told

The most up-to-date Advanced Life Support (ALS) algorithm. Use this at any stage during your Foundation Years; acutely unwell patients will be a common encounter and you should feel confident in determining whether a patient is cool or whether they need your help. If unsure, feel free to ask “are you cool?” Don’t be afraid to tell your patients to BE COOL.

There is no one way to be a good FY1, or house officer, as you will still find yourself referred to. However there are certain hints and tips that can be imparted by those that made it through. Intact. Unscathed. Ready to fight another day. ONWARD!

First and foremost, your first year as a doctor should be about enjoying yourself. Never forget this. There are many similarities to life at medical school; you will probably live in halls, go out too much and make lots of new friends. The only real differences are that you can’t bunk off anymore, but you do get paid.

The single greatest fear of a new doctor is that they will do some harm to a patient. This, whilst not impossible, is improbable. The reason being that you have spent four to six years learning how to do the opposite.

You are so imbued with misplaced self-doubt when you start working that you end up being over cautious. This is normal. Don’t worry about making mistakes, just concentrate on enjoying yourself and the rest will flow.

Perhaps the one gem of information I wish I had been given before I started was that you did not need to be top of the class at medical school to succeed in your first year of work.

In fact, where you ranked has no correlation whatsoever to how you will perform and you should put it out of your mind entirely.

If the comparison of FY1 to medical school can be extended, then the first week is Freshers’. With most junior medical staff now starting at the beginning of August every year, the hospital will be atwitter with introductions and nice-to-meet-yous when you start.

The first few days are rarely taxing. They normally consist of induction talks, orientation sessions and a gradual easing into the job.

You might turn out to be one of the unlucky punters that kicks off work with an on-call. Daunting it may be, but on-calls are fantastic learning opportunities. Asking for help is something you should never be afraid of doing in your first year. People will fully expect you to ask the most inane of questions, even if you feel like an idiot. Get over that embarrassment and ask – better that than goofing up something easy.

There is also no shortage of people to ask. Obviously your immediate seniors are a logical first step, but the resource you will invariably draw upon throughout your junior years is the nursing staff. If you take one piece of advice away from this article, make it this: be nice to nurses.

Nurses can make your life so much easier if you acknowledge their existence and value their contribution, and they can equally give you grief if you piss them off.

Nurses, like anyone else, don’t like being talked down to by snooty doctors. If you’re not sure what fluids to write up, or what the dose of metoclopramide is, asking a nurse is a good first move.

Having said that, nurses go through a learning process too and might be just as green as you. If you’re unsure about any advice given, there’s no harm getting a second opinion. You will find that the ability to know what is duff advice and what is good sense develops quickly and naturally.

A further word about those nurses. Most FY1s will be ward-based and whilst it is useful to be nice to nurses on-call, it is imperative to establish good relationships with the nurses on your own ward. They can be inordinately helpful if you’re mates. Not to mention that if you can have a laugh with the nurses, social workers, ward clerks, physios, OTs, HCAs or medical support workers on your ward, your job will all the more fun.

This provides a convenient segue onto what is likely to be the bane of your life during the Foundation Programme. Assessments. You thought tick-boxes and form-filling ended with graduation. I laugh at your foolishness.

Working well with those around you will stand you in very good stead for a key part of your overall assessment, the min-ePAT. Out of all the nonsense you are forced to complete in your first year, this is a very useful exercise.

On two occasions you are required to nominate twelve co-workers, of whom only a limited amount can be doctors, to anonymously say what they think about you. As you can imagine, the ability to be frank allows your colleagues to give you what can frequently turn out to be valuable advice.

All that need be said about the rest of your assessments is that the sooner you get them out of the way, the better. Try not to leave yourself a week to get all the forms filled in, it is no fun.

To reiterate, it is imperative you concentrate on having fun in your first year. It comes only once and just about every doctor you meet looks back on their house officer year with great nostalgia and fondness. No amount of hints and tips from seniors will replace your learning-by-doing, so try not to be wallflower.

If something that interests you is happening, be it inserting a central line or an appendicectomy, try to get involved. Be in the right place at the right time, but don’t be a dick – share out opportunities with friends.

Developing confidence comes far more easily to some than others, but ultimately the only occasion it matters is when a patient’s health is in question. If you are seeing someone in A&E or on the ward and you are unhappy about something, never worry about ‘bothering’ your seniors. Whilst it may be surprising to some, no one will criticise a new doctor for being too safe.

Lastly, if you are one of those keen young things that wants his or her name in lights, your first step would be to leave medicine. However if you want to stay, you might want to consider getting involved with an audit, a presentation or two (most hospitals expect a Grand Round presentation from all the juniors) and if you’re extra ambitious, a publication.

Having said all that, none of these are necessities. The only compulsory objectives for an FY1 are consolidating your medical knowledge (it’s up there somewhere, even if it doesn’t feel like it), seeing patients, getting organised, using your hands, extra-curricular high jinx and wild japes. These are integral to being a good doctor. Good luck and get ready to work like a HO.

Originally published in Quack: Foundation School Guide.

Diagram inspired by ALS guidelines and a flowchart from Antarctica, by Kim Stanley Robinson.

Labels: junior doctors, medicine

My regular column in Medical Student Newspaper has been reprised this academic year. This year it is, of course, 'F2. Woohoo.' Originally published in the October issue,

I’M CANCEROUS. Yes that’s right, I’m back for a fourth year running. This year, I come to you from the dizzy heights of the most superlative foundation doctor there is, THE MIGHTY F2.

A new generation of fresh-faced F1s replaced me and all my ilk. Now I’m supposed to know shit, you know, and stuff.

A&E’s a funny place to work. Over 90% of you will spend four months ‘on the medical front line’ as I am now. Unless you choose to pursue this field (ya crazy fool), your A&E rotation will be the job that brings you more excitement, boredom and frustration than any other. Mostly frustration.

No longer is the emphasis based on diagnosis, which is what draws so many into medicine, but on exclusion. Can you send this healthy 30 year-old chap home...are you SURE he hasn’t had an MI? Let’s refer him to the medics for a twelve-hour trop and take up a hospital bed just in case. It’s mind-numbingly un-stimulating at times.

There are many positives about working in A&E. Exposure to a wide range of problems, dealing with genuine emergencies, seeing instant results. My particular hospital has four great consultants and as St. George’s is a Centre of Excellence for countless specialties, I see some crazee sheeyrt.

However the one overwhelming negative is that it is A&E. There is no area of medicine that has been toyed with by the government as much as the emergency department.

Because waiting times are so easy to quantify and brag about before an election, A&E is a convenient place to pull numbers from. It is also one of two first points of contact for patients. The other is, of course, general practice, which has been tinkered with almost as much, chiefly to the detriment of A&E departments.

The ridiculous lack of sufficient out-of-hours GP provision, NHS dentists, the creation of stop-gaps like NHS Direct and obscene waits for GP appointments mean we are inundated with complaints that are neither accidents nor emergencies.

Yet each person that attends A&E has to be seen, diagnosed, treated and moved out of the department in four hours.

As all five Rohinplasty readers will know (it’s going up), I am obsessed with a solid evidence base. I use that as a chat up line sometimes. Anyway, one would like to think that those responsible for these four hours used all the available data to construct a sophisticated model of a working A&E and thus extrapolated a suitable figure.

The truth is probably more along the lines of pin-the-tail-on-the-number, with an arbitrary figure being plucked from the air.

The reality is a shambles. Of course no standard duration can be applied to A&E patients, as there is no one type of A&E patient. Some are out within ten minutes but some need several hours.

A far more sensible system, as I’m sure an honest government would concede, would consist of clinicians deciding how long each patient needed to be safely dealt with.

However politicians make decisions, not doctors, so that ‘four hour waits’ can be political weapons.

Only 2% of patients are allowed to ‘breach’.

I figured, like many others, a cavalier attitude was the way forward and thought I would ignore breaches and put the patient first. The NHS doesn’t work that way.

Unwell patients often need to stay in A&E until they are stable enough to be transferred. Pissheads need to sober up before they go.

The Medical Assessment Unit, or MAU, that most of you will be familiar with by now, owes its existence to the four-hour-wait. MAUs were created to stop the clock. The vast majority of patients admitted to a hospital come under the care of the general physicians. Hence all medical patients now go to MAUs where there is no timer.

There is no guarantee they will be adequately treated by the time they arrive there and there is no guarantee they will be seen by the doctors looking after them, hence negating the entire reason for the four hour rule.

I must be careful with what I say about my employer, so suffice it to say that unfortunately cooking the books MAY OR MAY NOT OCCUR at SOME hospitals around the country. Will that sound sufficiently vague in court?

Picture the scene. A patient needs a urine dipstick to make a diagnosis of a UTI. However a nurse is off sick and the nursing staff is over-stretched. No one gets the urine sample. The patient breaches. If this breach were recorded perhaps management would see that missing nurse’s value.

However if the number of breaches is the same as on any other night, the hospital realises she’s unnecessary and sacks her. They congratulate each other on more money saved. The system is broken, nothing changes.

We have some bizarre A&E mentality now that stipulates the customer is always right. But the patient is rarely first.

Nurses will drive you slowly mad with a phrase you will quickly grow tired of, “come on, your patient’s about to breach.” I normally cave.

Title reference to Nine Hours to Rama.

Labels: A+E, medicine, NHS, Rohinplasty articles

SIXTY years of a free

"We have hard work ahead"

Amartya Sen, a man who has watched

He wrote this on the 50th anniversary of Indian independence and essentially concluded whilst democracy was intact in

Sunny Hundal, another famous thinker, said in response to Part One that "religious minorities in

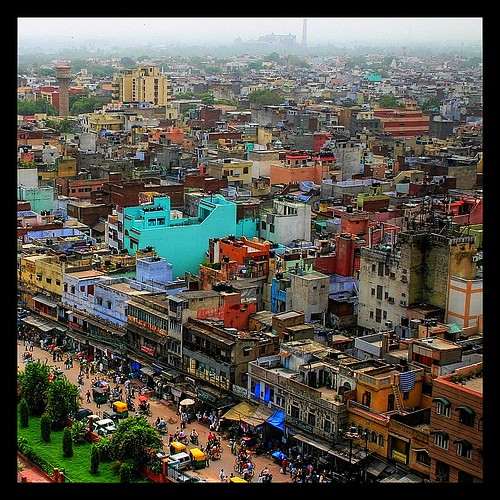

Take the example of

For the best part of twenty years, UP had been ruled by coalitions, most recently dominated by the BJP and the Samajwadi Party. Despite the majority of UP residents being woefully uneducated, the voters turned out in force earlier this year and swept one party, the once insignificant Bahujan Samaj, into power with an absolute majority.

The socialist-leaning party was created in 1984 to empower the dalits (untouchables) but campaigned on a platform of social justice which transcended caste and class. UPians, sick of politicians exploiting caste divides, replaced the old with the new.

"To build up a prosperous, democratic and progressive nation"

Indian democracy's downfall has oft been predicted, at no point more assuredly than when Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in 1975. As dissenting voices rose, the government took steps to quash any opposition. Sanjay engineered a forced sterilisation programme and brutally cleared the slums surrounding

Ultimately, Gandhi's contravention against the Indian belief of freedom of the press was her downfall. By censoring newspapers she astonishingly misjudged her popularity and when elections were called in 1977, the Janata Party washed her out of power. Good came from the unfortunate episode, the electorate had spoken.

Democracy, viewed by much of the world as Western hegemony, is alive (but not necessarily well) in

However a liberal democracy alone does not a successful country make. Corruption continues to pervade every aspect of Indian society (the fairytale story in UP is somewhat spoiled by corruption allegations surrounding the leader of the BSP) and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

"The ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity"

Some figures.

| Population growth rate 1.6% Median age 24.8 Life expectancy 68.6 GDP growth rate 9.2% GDP per capita $3800 Literacy: 61% (male 73.4%, female 47.8%) | Population growth rate 0.6% Median age 33.2 Life expectancy 72.9 GDP growth rate 10.7% GDP per capita $7,700 Literacy: 90.9% (male 95%, female 86.5%) |

The statistic that leaps from that table is

Today Manmohan Singh said his country will not be truly free until poverty is eradicated. This will not happen for many years. He pledged to put an end to malnutrition by 2012. Whilst this too seems like fanciful thinking, for the first time in most Indian's living memory, there is a genuine belief good things will happen.

Yet these schools are under-funded and in a state of disrepair. Without a basic level of education, a wider interaction with

It has been demonstrated that

The Indian entrepreneurial spirit has captured the imagination of the financial media around the world. Lakshmi Mittal is now the fifth richest man in the world and he is one of the faces responsible for Indian business being viewed in a new light.

The West had just grown accustomed to

The Reliance Group, divided by fighting brothers Mukesh and Anil, looks set to unleash supermarkets and more mobile phones on Indian consumers itching to spend.

I am conscious that as an Indian-born NRI it is easy to don rose-tinted glasses and turn a blind eye to the widespread suffering ever-present in

Atanu Dey and Reuben Abraham, Mumbai economists, suggest that the best way ahead for the hundreds of thousands of villages and the handful of teeming, unplanned urban sprawls which live in coexistence now is to reach a compromise.

Along with education, perhaps

I follow

Global centres of excellence are built with the government assistance, on the agreement they will run a 'poor ward' or two. News agencies like NDTV have revealed these wards are routinely empty, treating ministers' families or filled with foreign, paying, visitors.

"Fullness of life to every man and woman"

Much is made of the ascendancy of women. The new President is Pratibha Patil. She advocated sterilising those with genetic disease. However, she did found a bank to empower women in the 1970s. A good role model for Indian girls. Well, she stole millions not only from her empowered female customers, but also a sugar factory and a charitable trust. Some role model.

In yesterday's Guardian, Sagarike Ghose, presenter on CNN's Indian counterpart, worries the Indian women's movement has lost its way. Perceived early successes have led to a backlash against 'feminist types'. Young women see individual freedom (to smoke, wear short skirts, get laid) as more important than a collective freedom to express themselves as half the country's population.

Of course, whilst practices like female foeticide, acid attacks and honour killings continue, women may make up less than 50% of the population.

Ghose states that as Indian feminism failed to have a clear goal, young Indian girls have adopted a beautiful and vapid role model to aspire to. She makes a great point that certainly rings true to me, that of the pseudo-traditionalist:

The heroines of "newIndia " films were presented not as individuals attempting to create their own lives in a new economy, as millions of women acrossIndia were doing. Instead, the films showed young brides following religious ritual down to the last detail - viewing the moon through a sieve, praying before their in-laws' photographs, and spending their girlhoods working towards getting a husband.

When I met students at a prestigious women's college atDelhi University last month, the majority told me that they wanted to get married to a rich man and have week-long weddings, with all the rituals, because that was part of "Indian tradition". They didn't want to be the "feminist type".

This notion is, no doubt, fuelled by another Indian behemoth, the TV industry. Few realise that television revenues this year will be around £3 billion, double that of Bollywood. I've watched the soaps that grip

Masterminding the televisual revolution sweeping

"We rejoice in that freedom, even though clouds surround us"

A tumultuous sixty years promises much ahead.

Picture credits, from top:

Tricolour, artsander

Paperboy, Calamur

KK Menon, gaurang

India economics, TIME.com

Tata truck, Calamur

Demure, Letha Jose

Diversity Writer of the Year

Runner-up Columnist of the Year

Nominated Features Writer of the Year

It's the Pirates

Yam Boy

Video Wallah

Shiva Soundsystem

Within / Without

Saheli Datta

Random Acts of Reality

NHS Blog Doc

The Oracle

Turbanhead

HERStory

Ethno Techno

2. Rohinplasty (series)

3. Medical student teaching (series)

4. What your stetho says about you

5. Revision: IT BRINGS DEATH

6. Things you kids won't see (series)

7. Tsunami Politics

8. Churchill: Let the fakir die

9. If it looks like a quack...

10. Ten million missing girls

Real Doctor

They hate you

Incendiary views

Scrooge McDoc

Suspicious behaviour

The Renal Angle

The bastard son of MTAS

All Hallow's A&E

Quack

August 2005

September 2005

October 2005

November 2005

December 2005

January 2006

February 2006

March 2006

April 2006

May 2006

June 2006

November 2006

December 2006

February 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

October 2007

November 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

July 2008

December 2008

-->