The Daily Rhino

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

"A new star rises" - Part Two

SIXTY years of a freeIndia have passed. Where is it now?

Amartya Sen, a man who has watchedIndia change over this time, divided an assessment of India 's progress since Independence into three categories. First, the practice of democracy, second the removal of social inequality and backwardness and lastly the achievement of economic progress and equity.

He wrote this on the 50th anniversary of Indian independence and essentially concluded whilst democracy was intact inIndia , it was failing on the second count. India's economy, of which we hear so much today, was beginning to gather pace in 1997, but it is surprising that the monumental leaps and bounds the GDP and purchasing power have made occurred in only the last decade.

Sunny Hundal, another famous thinker, said in response to Part One that "religious minorities inIndia snort in derision when India is declared as a democracy." Well, they may scoff all they like, but the democracy central to Gandhi and Nehru's aspirations for India is standing tall.

Take the example ofIndia 's Texas . Uttar Pradesh is the biggest, most powerful and most backward state (excepting Bihar ). It has produced eight Indian prime ministers and has a population larger than Pakistan .

For the best part of twenty years, UP had been ruled by coalitions, most recently dominated by the BJP and the Samajwadi Party. Despite the majority of UP residents being woefully uneducated, the voters turned out in force earlier this year and swept one party, the once insignificant Bahujan Samaj, into power with an absolute majority.

The socialist-leaning party was created in 1984 to empower the dalits (untouchables) but campaigned on a platform of social justice which transcended caste and class. UPians, sick of politicians exploiting caste divides, replaced the old with the new.

Indian democracy's downfall has oft been predicted, at no point more assuredly than when Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in 1975. As dissenting voices rose, the government took steps to quash any opposition. Sanjay engineered a forced sterilisation programme and brutally cleared the slums surroundingDelhi 's Jama Masjid. Political dissenters were arrested and tortured.

Ultimately, Gandhi's contravention against the Indian belief of freedom of the press was her downfall. By censoring newspapers she astonishingly misjudged her popularity and when elections were called in 1977, the Janata Party washed her out of power. Good came from the unfortunate episode, the electorate had spoken.

Democracy, viewed by much of the world as Western hegemony, is alive (but not necessarily well) inIndia . Parties have won votes and come into power. They have lost and stepped aside. The press is free to criticise.

However a liberal democracy alone does not a successful country make. Corruption continues to pervade every aspect of Indian society (the fairytale story in UP is somewhat spoiled by corruption allegations surrounding the leader of the BSP) and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Some figures.

The statistic that leaps from that table isChina 's literacy rate. The two Asian powerhouses have a healthy economic rivalry, but China 's overall education rate leaves India 's in the dust. The number of university graduates in India conversely dwarves the number in China , but inequality abounds. Kerala's life expectancy and literacy surpass China 's, Bihar 's rank lower than Bangladesh .

Today Manmohan Singh said his country will not be truly free until poverty is eradicated. This will not happen for many years. He pledged to put an end to malnutrition by 2012. Whilst this too seems like fanciful thinking, for the first time in most Indian's living memory, there is a genuine belief good things will happen.

China is not a democracy. But it has succeeded in spreading the wealth to a greater extent than India . Indian commentators may seize upon the fact that China 's growth has created millions of disenfranchised migrant workers and peasants, but poverty (which was on a similar scale to India in the first half of the last century) has been combated far more effectively. Why?

China is a global heavyweight in exporting manufactured goods. Whilst India exports IT and scientific expertise, much of China 's overseas business relies on 'unskilled' labour. Unskilled, but not unschooled. Chinese industry employs tens of millions - literate, schooled workers but not university graduates.

India 's higher education establishments have gained deserved worldwide accolade, but studying at IIT or IIM is a dream achieved by a tiny minority in India . Emphasis needs to be placed upon improving India 's schools. If one examines the syllabus at a typical secondary school in rural India , it is truly shocking to see how far ahead Indian schoolchildren are than their Western peers. Or rather, it's depressing to see how Britain 's schools have dumbed down.

Yet these schools are under-funded and in a state of disrepair. Without a basic level of education, a wider interaction withIndia 's economic success story will not be possible. The 'trickle-down' effect will take too long and much of India 's poor will never receive so much as a drop without a concerted effort to equalise the wealth.

It has been demonstrated thatChina can enjoy the same - if not more - success without the joys of democracy, so should its perseverance in India continue to be a thing of pride? Democracy, at a basic level, acts as a safety check. Leaders have to act decisively in times of crisis, or risk falling from grace. Returning to Amartya Sen, he achieved fame many years ago by reasoning that famines were a political product, not an agricultural one.

India , previously ravaged by famines, has not suffered one since Independence . Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward is regarded as a massive economic blunder, but it's also one that killed over 20 million Chinese by causing the Great Chinese Famine. Amartya Sen credits democracy for this not being repeated in India .

The Indian entrepreneurial spirit has captured the imagination of the financial media around the world. Lakshmi Mittal is now the fifth richest man in the world and he is one of the faces responsible for Indian business being viewed in a new light.

The West had just grown accustomed toIndia becoming the world's back office, but now Indian businesses have developed a bona fide reputation as predatory. Mittal's acquisition of Arcelor and the biggest Indian takeover of a foreign company, Tata's buyout of Corus, have worried complacent Western CEOs.

The Reliance Group, divided by fighting brothers Mukesh and Anil, looks set to unleash supermarkets and more mobile phones on Indian consumers itching to spend.

I am conscious that as an Indian-born NRI it is easy to don rose-tinted glasses and turn a blind eye to the widespread suffering ever-present inIndia . Concordantly, urban Indians can romanticise the lives of their rural compatriots, conjuring a pleasant country life and oblivious to the fact many of their forebears fled those very conditions for the city.

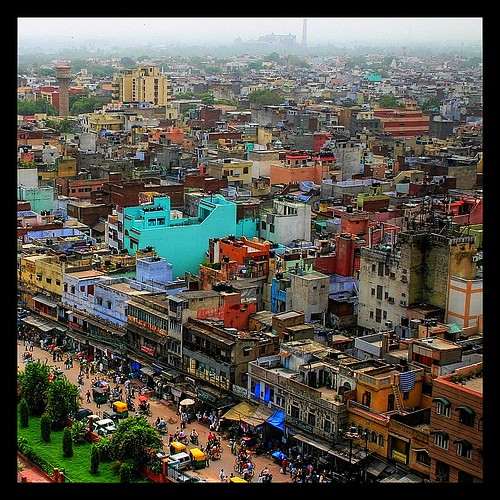

Atanu Dey and Reuben Abraham, Mumbai economists, suggest that the best way ahead for the hundreds of thousands of villages and the handful of teeming, unplanned urban sprawls which live in coexistence now is to reach a compromise.India must create new urban centres to relieve the pressure still exacted upon the major cities by unchecked and overwhelming migration.

Along with education, perhapsIndia 's two greatest challenges are cementing the equal position of women in society and providing adequate healthcare to the masses.

I followIndia 's medical breakthroughs and shortcomings with interest. It is a familiar story, of world-beating advances and horrific inadequacy. It may surprise some that I am realistically considering pursuing a career in an Indian hospital, but the factor holding me back is an uncertainty that I could work knowing that, unless I work in a decrepit public hospital, I will only be treating the rich, be they Indian or visiting health tourists.

Global centres of excellence are built with the government assistance, on the agreement they will run a 'poor ward' or two. News agencies like NDTV have revealed these wards are routinely empty, treating ministers' families or filled with foreign, paying, visitors.India will soon have more HIV sufferers than any other country. Little is being done to prevent this.

Much is made of the ascendancy of women. The new President is Pratibha Patil. She advocated sterilising those with genetic disease. However, she did found a bank to empower women in the 1970s. A good role model for Indian girls. Well, she stole millions not only from her empowered female customers, but also a sugar factory and a charitable trust. Some role model.

In yesterday's Guardian, Sagarike Ghose, presenter on CNN's Indian counterpart, worries the Indian women's movement has lost its way. Perceived early successes have led to a backlash against 'feminist types'. Young women see individual freedom (to smoke, wear short skirts, get laid) as more important than a collective freedom to express themselves as half the country's population.

Of course, whilst practices like female foeticide, acid attacks and honour killings continue, women may make up less than 50% of the population.

Ghose states that as Indian feminism failed to have a clear goal, young Indian girls have adopted a beautiful and vapid role model to aspire to. She makes a great point that certainly rings true to me, that of the pseudo-traditionalist:

This notion is, no doubt, fuelled by another Indian behemoth, the TV industry. Few realise that television revenues this year will be around £3 billion, double that of Bollywood. I've watched the soaps that gripIndia - it's an experience I would not wish upon my worst enemy - and every female character is truly depressing.

Masterminding the televisual revolution sweepingIndia are people like former rice salesman Subhash Chandra, chair of Zee TV. Television sets are becoming more affordable and more ubiquitous. Seasoned industrialist Ratan Tata wants to go even further with his plans to unveil an ultra-cheap car for the masses. The carbon footprint of millions more with a shiny new car will be a crater.

A tumultuous sixty years promises much ahead.India is developing into a great nation, albeit one wracked with problems. As it teeters on the brink of superpowerdom, it is far from the India Gandhi had envisioned. But on this anniversary a genuine hope and optimism drift above a fascinating process of growth. India may be 60 years of age, but looking at the faces that will shape its next 60, it is young.

Picture credits, from top:

Tricolour, artsander

Paperboy, Calamur

KK Menon, gaurang

India economics, TIME.com

Tata truck, Calamur

Demure, Letha Jose

SIXTY years of a free

"We have hard work ahead"

Amartya Sen, a man who has watched

He wrote this on the 50th anniversary of Indian independence and essentially concluded whilst democracy was intact in

Sunny Hundal, another famous thinker, said in response to Part One that "religious minorities in

Take the example of

For the best part of twenty years, UP had been ruled by coalitions, most recently dominated by the BJP and the Samajwadi Party. Despite the majority of UP residents being woefully uneducated, the voters turned out in force earlier this year and swept one party, the once insignificant Bahujan Samaj, into power with an absolute majority.

The socialist-leaning party was created in 1984 to empower the dalits (untouchables) but campaigned on a platform of social justice which transcended caste and class. UPians, sick of politicians exploiting caste divides, replaced the old with the new.

"To build up a prosperous, democratic and progressive nation"

Indian democracy's downfall has oft been predicted, at no point more assuredly than when Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in 1975. As dissenting voices rose, the government took steps to quash any opposition. Sanjay engineered a forced sterilisation programme and brutally cleared the slums surrounding

Ultimately, Gandhi's contravention against the Indian belief of freedom of the press was her downfall. By censoring newspapers she astonishingly misjudged her popularity and when elections were called in 1977, the Janata Party washed her out of power. Good came from the unfortunate episode, the electorate had spoken.

Democracy, viewed by much of the world as Western hegemony, is alive (but not necessarily well) in

However a liberal democracy alone does not a successful country make. Corruption continues to pervade every aspect of Indian society (the fairytale story in UP is somewhat spoiled by corruption allegations surrounding the leader of the BSP) and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

"The ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity"

Some figures.

| Population growth rate 1.6% Median age 24.8 Life expectancy 68.6 GDP growth rate 9.2% GDP per capita $3800 Literacy: 61% (male 73.4%, female 47.8%) | Population growth rate 0.6% Median age 33.2 Life expectancy 72.9 GDP growth rate 10.7% GDP per capita $7,700 Literacy: 90.9% (male 95%, female 86.5%) |

The statistic that leaps from that table is

Today Manmohan Singh said his country will not be truly free until poverty is eradicated. This will not happen for many years. He pledged to put an end to malnutrition by 2012. Whilst this too seems like fanciful thinking, for the first time in most Indian's living memory, there is a genuine belief good things will happen.

Yet these schools are under-funded and in a state of disrepair. Without a basic level of education, a wider interaction with

It has been demonstrated that

The Indian entrepreneurial spirit has captured the imagination of the financial media around the world. Lakshmi Mittal is now the fifth richest man in the world and he is one of the faces responsible for Indian business being viewed in a new light.

The West had just grown accustomed to

The Reliance Group, divided by fighting brothers Mukesh and Anil, looks set to unleash supermarkets and more mobile phones on Indian consumers itching to spend.

I am conscious that as an Indian-born NRI it is easy to don rose-tinted glasses and turn a blind eye to the widespread suffering ever-present in

Atanu Dey and Reuben Abraham, Mumbai economists, suggest that the best way ahead for the hundreds of thousands of villages and the handful of teeming, unplanned urban sprawls which live in coexistence now is to reach a compromise.

Along with education, perhaps

I follow

Global centres of excellence are built with the government assistance, on the agreement they will run a 'poor ward' or two. News agencies like NDTV have revealed these wards are routinely empty, treating ministers' families or filled with foreign, paying, visitors.

"Fullness of life to every man and woman"

Much is made of the ascendancy of women. The new President is Pratibha Patil. She advocated sterilising those with genetic disease. However, she did found a bank to empower women in the 1970s. A good role model for Indian girls. Well, she stole millions not only from her empowered female customers, but also a sugar factory and a charitable trust. Some role model.

In yesterday's Guardian, Sagarike Ghose, presenter on CNN's Indian counterpart, worries the Indian women's movement has lost its way. Perceived early successes have led to a backlash against 'feminist types'. Young women see individual freedom (to smoke, wear short skirts, get laid) as more important than a collective freedom to express themselves as half the country's population.

Of course, whilst practices like female foeticide, acid attacks and honour killings continue, women may make up less than 50% of the population.

Ghose states that as Indian feminism failed to have a clear goal, young Indian girls have adopted a beautiful and vapid role model to aspire to. She makes a great point that certainly rings true to me, that of the pseudo-traditionalist:

The heroines of "newIndia " films were presented not as individuals attempting to create their own lives in a new economy, as millions of women acrossIndia were doing. Instead, the films showed young brides following religious ritual down to the last detail - viewing the moon through a sieve, praying before their in-laws' photographs, and spending their girlhoods working towards getting a husband.

When I met students at a prestigious women's college atDelhi University last month, the majority told me that they wanted to get married to a rich man and have week-long weddings, with all the rituals, because that was part of "Indian tradition". They didn't want to be the "feminist type".

This notion is, no doubt, fuelled by another Indian behemoth, the TV industry. Few realise that television revenues this year will be around £3 billion, double that of Bollywood. I've watched the soaps that grip

Masterminding the televisual revolution sweeping

"We rejoice in that freedom, even though clouds surround us"

A tumultuous sixty years promises much ahead.

Picture credits, from top:

Tricolour, artsander

Paperboy, Calamur

KK Menon, gaurang

India economics, TIME.com

Tata truck, Calamur

Demure, Letha Jose

Comments:

Damn boy, you gonna make a grown man cry.

If we ever had a Kennedy it was Rajiv Gandhi, scandals and all. I still remember the guy on tv, even though i was barely 3 or 4 years old. We seriously need someone young in the Rahstrapati Bhawan.

Post a Comment

If we ever had a Kennedy it was Rajiv Gandhi, scandals and all. I still remember the guy on tv, even though i was barely 3 or 4 years old. We seriously need someone young in the Rahstrapati Bhawan.

Diversity Writer of the Year

Runner-up Columnist of the Year

Nominated Features Writer of the Year

It's the Pirates

Yam Boy

Video Wallah

Shiva Soundsystem

Within / Without

Saheli Datta

Random Acts of Reality

NHS Blog Doc

The Oracle

Turbanhead

HERStory

Ethno Techno

2. Rohinplasty (series)

3. Medical student teaching (series)

4. What your stetho says about you

5. Revision: IT BRINGS DEATH

6. Things you kids won't see (series)

7. Tsunami Politics

8. Churchill: Let the fakir die

9. If it looks like a quack...

10. Ten million missing girls

Who needs the Kwik-E-Mart?

Try before you prescribe

Shilpa and Shakespeare cockroaches

SHO me the exit

Someday you realise your Mum's not going to live f...

The beginner's guide to the MTAS fiasco

The student becomes the master. THE MASTER I TELL ...

Patrica Blewitt

BUY. MY. BOOK.

August 2005

September 2005

October 2005

November 2005

December 2005

January 2006

February 2006

March 2006

April 2006

May 2006

June 2006

November 2006

December 2006

February 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

October 2007

November 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

July 2008

December 2008

-->